Beat the COVID-19 blues! Keep your book club active.

Reading Between the Wines...

These ladies know how to make someone feel welcome!

Last Thursday, my wife and I attended the “Reading Between the Wines” book club in Austin to discuss my novel, Death in Panama. They prepared a fantastic dinner, including empanadas and patacones! But the best treat of the evening was hearing the enthusiasm they had for my book.

They asked a lot of insightful questions, indicating their experience in reading the book was what I’d hoped for. I wanted to tell an entertaining and interesting story and yet provide readers with more; namely, complex, realistic characters dealing with personal problems and ethical dilemmas that challenge readers to consider how they would deal with similar situations.

Thank you, ladies.You got it.You made my day!

Are we being too sensitive?

Barely a day goes by that someone is not in the news, apologizing about something or being told they should.

The latest example is Ilhan Omar, a Congresswoman from Minnesota, who has been accused of making anti-Semitic remarks. Before that, it was sixteen-year-old Nick Sandmann, who was part of a group of Catholic high-school students waiting on their bus in front of the Lincoln Memorial. When a video of Nick surfaced, showing him wearing a MAGA hat and smiling at a Native American activist who approached the group of boys, he was lambasted by social media, as well as mainstream outlets such as the Washington Post and CNN. They accused him of being a racist and the product of “white privilege,” among other things. Nevertheless, a quick look at the entire video shows Nick did nothing wrong. The media grossly overreacted.

But my purpose here is not to debate whether Ms. Omar’s comments were inappropriate or merely an expression of her views on U.S. policy toward Israel. Nor am I going to comment on whether Mr. Sandmann will—or should—be successful in his lawsuits against the Washington Post and CNN. My purpose here is, in part, to point out that such events seem to dominate public discourse much more than important issues, such as our country’s relationships with China and North Korea, for example.

Why is it that so many people seem to be fixated on who owes whom an apology?

The political commentator George F. Will described it this way:

“The cultivation - even celebration - of victimhood by intellectuals, tort lawyers, politicians and the media is both cause and effect of today’s culture of complaint.”

It wasn’t always this way. There was a time, not too long ago, when folks didn’t take themselves so seriously. Now, it seems, you can find yourself offending someone without even realizing it.

The comedian, Jerry Seinfeld, has stopped performing at college campuses because they are “too politically correct.” As he explained, “College students throw around ‘that's racist / sexist / prejudice’ without knowing what they're talking about.”

Even Dr. Seuss has come under fire. Researchers Katie Ishizuka and Ramón Stephens recently published the results of their study of his iconic children’s books in an article titled: “The Cat is Out of the Bag: Orientalism, Anti-Blackness, and White Supremacy in Dr. Seuss's Children's Books.” The title says it all.

Where does all of this end?

There’s no doubt that our society has become hyper-sensitive. Clearly, many folks need to take a deep breath and “lighten up.” But pendulums have a way of swinging to the extremes. Some of the ridiculous claims of victimhood and calls for apologies could cause a backlash, which wouldn’t be good for our society either. If we start dismissing calls for apologies—even reasonable ones—as simply more chatter from the “snowflake generation,” then we run the risk of not apologizing in instances when we should.

So that begs the question: When should we apologize?

The simple answer is that one should apologize when he or she has wronged someone else. Sometimes, it is obvious when that happens. Many times, it’s not.

Deciding whether one has wronged someone else requires careful thought about whether it is reasonable to conclude that something one has said or done is offensive. But as any lawyer will tell you, what is “reasonable” depends on innumerable factors. So, perhaps the answer is not so simple.

No doubt, questions of right and wrong can be clear. No one would argue that murder is acceptable, for example. But there are grey areas, and they seem to be expanding rapidly. Should I apologize for being insensitive to another’s political beliefs if I disagree with them? What about religion? Although most people refrain from making derogatory remarks about another’s religion, we’ve all heard jokes involving the Pope or Baptists or Jews or fill-in-the blank.

To some extent the answer lies in considering how much another person might identify with something; that is, how much it is a part of who they are. If it is something immutable, such as the color of a person’s skin, then making that characteristic the butt of a joke is clearly insensitive.

But what if someone takes himself too seriously? Is it really reasonable to conclude Dr. Seuss was a racist, sexist, xenophobe? Or that the Washington Redskins should change their name because it’s offensive? Is an apology called for when someone is offended because he takes himself too seriously? Probably not. But who decides if someone is taking himself too seriously?

Politics are another matter, in my humble opinion. Having strongly held beliefs should simply mean you’re ready to defend them. Political beliefs do not define an individual, as evidenced by the transformation of some public figures such as Ronald Reagan and Thomas Sowell, each of whom started his adult life as liberal and later became an ardent conservative. To me, one’s politics are fair game for criticism, and if someone doesn’t like it, then . . . well . . . he can lump it. That said, I also believe that a political argument should never destroy, or even undermine, one’s relationship with a family member or friend. And, the discourse should be respectful, not ad hominem.

So I guess I can’t offer clear guidance about when one should apologize, other than to say we should each examine our own heart. I was prompted to write this blog post, because I recently had an occasion to do just that.

As the readers of my novel Death in Panama know, it is loosely based on my experiences while stationed in Panama where I prosecuted a murder case. The novel also makes observations on Army life and briefly on Panamanian society and life in the Canal Zone.

To my dismay, I received an email from a reader who grew up in the Canal Zone and felt that my portrayal of Zonians was insulting. It would have been easy for me to dismiss her complaint, especially since much of the book, including some of the stories about Zonians, is based on my actual experiences in Panama. But I didn’t do that. Instead, I tried to understand why she might have been offended and concluded that her complaints were justified. So, I apologized. Later, I began to wonder whether other readers might be similarly offended, in particular because last summer I sold a number of copies of my book at the Panama Canal Society Reunion. So, I decided to publish an open letter to the Society in an effort to explain myself.

I’m not suggesting I’m any sort of “good guy” for apologizing. On the contrary, the author of the email was correct: I should have been more sensitive, especially with regard to something so personal as someone’s identity; that is, being a “Zonian.”

Questions of right and wrong are as old as time. I’ve concluded that there are no easy answers for many of them. All that well-intentioned people can do is try to be sensitive and respectful of others; refrain from taking themselves too seriously; and most important, as the Good Book says: “be quick to listen, slow to speak and slow to become angry.”

Renaissance Man

My wife and I have begun a book tour out West. Our first stop was in El Paso, Texas, where we stayed with my West Point classmate, Dr. Stephen P. Hetz, MD, Colonel, US Army (Retired), and his wife Mary.

One of the greatest blessings I’ve received in my life is being a member of the West Point Class of 1975. I entered the class on a stormy July 1, 1971, with no brothers of my own and graduated on a sunny day four years later with 862. They are my closest friends and have been with me through thick and thin.

Steve is a special friend. We went to through all the challenges West Point had to offer, but also got to go helicopter school after our second academic year, known as Yearling Year. We went to Fort Wolters, Texas, for instruction and logged over forty hours on the Army’s TH55 training helicopters, known affectionately as "Mattel Messerschmitts."

Years after graduation I encountered Steve again at Fort Gordon, Georgia. By then he was an Army surgeon, and my wife was in need of an appendectomy. Because of our relationship, Steve didn’t perform the surgery, but he ensured that everything went smoothly and was there for me during that stressful situation. A few months later, he was there for me again when I needed surgery and ensured that I was well taken care of.

I entitled this post “Renaissance Man” because Steve is exactly that. After graduation, he was commissioned as an Infantry officer. He graduated from Ranger School and served in the 82nd Airborne Division. Later, he participated in a highly competitive program, was selected to attend medical school, and became an Army doctor. In December 1989, as a medical doctor, he parachuted into Panama with Army Rangers as part of Operation Just Cause. That action earned him a gold star on his Master Parachutist Badge—a rare award for an Army doctor. He went on to earn a reputation as one of the Army’s outstanding surgeons. He had combat tours in Iraq and Afghanistan and was one of the authors of a highly regarded treatise, entitled War Surgery in Afghanistan and Iraq: A Series of Cases, 2003-2007.

On this most recent trip, I learned that Steve has yet another talent of which I was unaware. The airplane in the picture is an experimental airplane that he built by himself while working full time as a civilian surgeon at William Beaumont Army Medical Center in El Paso. I was astounded when he described the process of assembling the plane, which he accomplished in only two years. Because the airplane is experimental, he must log forty hours before he can take passengers. He’s working toward that goal, and I look forward to the day when he flies to Georgetown, Texas, and gives me a ride.

Courage and Drive ’75!

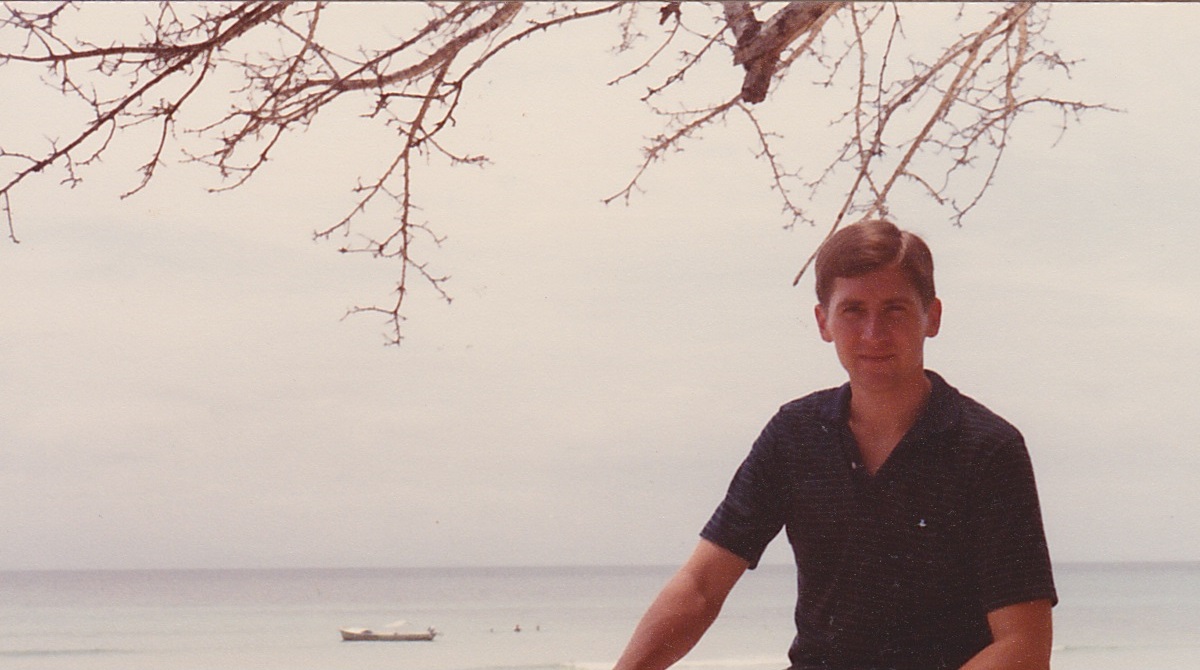

Reminiscing About Old Times

While cleaning out a closet, I came across some old photos from my time in Panama. (Click on the photo to advance the carousel.) It reminded me of what a wonderful experience it was, although I don’t remember looking like a kid. As I’ve mentioned before, Death in Panama is loosely based on my experiences in Panama in the early 1980s. There were some really good times, as evidenced by the smile on my face in some of these pictures, but there were also some gut-wrenching emotional times. The murder trial, on which much of Death in Panama is loosely based, was one of those times.

By the way, the protagonist in Death in Panama, Robert E. Clark, is a lot more handsome than yours truly.

The Faces of Poverty

Before I moved to Panama in 1982, I thought I knew what poverty was. I didn’t. As recounted in Death in Panama and in other blogs on this Web site, the sights, sounds, and smells of Panama’s poverty were heartbreaking. But I was only an observer from afar. I understood very little about poverty until much later.

By 1997, I had left active duty in the Army and moved my family to an Atlanta suburb. We went to a church where the parking lot was full of late-model cars, and the pews were full of freshly scrubbed and well-dressed worshippers. One Sunday, the pastor made an announcement about a “mission” trip to Honduras. As I was to learn later, the “mission” was one of assistance, not spreading the Gospel: the people we helped in Honduras were already well aware of God’s word. In fact, they knew it better than most of us who went on that mission trip.

That summer, a team of about fifteen men and women went to a small town near La Ceiba, Honduras, where we helped to rebuild a church that had been almost demolished by a storm. Every day, we labored in the searing sun, building pews and putting a new roof on the structure. We had to wear gloves when we worked on the roof, because the metal got too hot to touch. We worked side-by-side the members of the church, most of whom were taking time away from jobs, thereby reducing their already meager incomes. There was a language barrier, of course, but we worked through that with lots of smiles and what looked like a continuous game of Charades.

That trip to Honduras was followed by four mission trips to Peru. On the last two, I took my youngest daughter, who was fourteen years old during her first trip and fifteen on her last. We visited an orphanage in Lima and travelled by bus over a two-lane, winding road up the Andes Mountains—over 15,000 feet—and down the other side to a little town called San Ramon. Just as I had in Honduras, my daughter and I worked and worshipped with people who were struggling to survive.

One morning, a tiny, elderly lady appeared at the worksite with a pitcher of orange juice that was almost half her size—her gift to her friends from North America. She walked around and gave each of us a cupful. We later learned that she lived in a shack with a dirt floor. She had arisen before dawn and gone into the jungle to pick the oranges she used to make her gift. The fresh juice was unbelievably good—a far cry from the pale substitute we normally get from a frozen can. We concluded that it was more wonderful than any we’d ever had, because of the love that must have gone into it.

I learned some valuable lessons during those trips to Honduras and Peru. I learned that I’m extremely lucky to have been born where I was. I now understand—in ways that are unforgettable—that the opportunities all of us take for granted are unknown to most of the world. In addition, poverty is no longer an abstract concept for me. It has a human face—many human faces. My Bible bears inscriptions from Cinthya Bazán and Victor Ramirez and many other friends I will probably never see again. But they touched my heart in ways that are difficult to describe. They are people who—just like me—are trying to make their way in the world, although their paths are much tougher than mine.

Life has shown me that sometimes people are poor because they’ve made bad choices or simply had bad luck. Many other times—in places like Panama and Honduras and Peru—nothing they can do will change their circumstance. If they are born into poverty, there is little chance they will escape it. Nevertheless, they are human beings who love and laugh and hurt and cry. And, they hope that somehow tomorrow will be a better day.